Mongolian Grammar

Mongolian Grammar

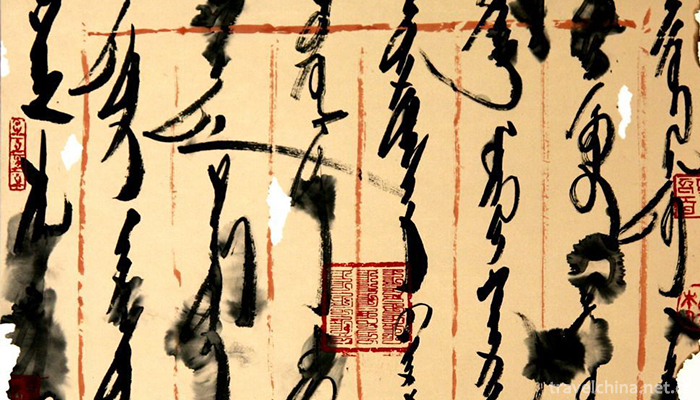

Mongolian traditional calligraphy also pays attention to the skills of moving pens, such as astringent two-way pen, backhand pen, towing pen, effect pen, horizontal pen, etc. In ink, there are full pen, thirsty pen and astringent pen.

Mongolian Calligraphic Law was selected into the fourth batch of representative projects of national intangible cultural heritage in 2014.

Historical origin

Before the 13th century, there was no unified written language among the Mongolian nationalities in the Mongolian Plateau. Genghis Khan has a history of more than 800 years since he borrowed the Huihe Mongolian script to complete the cause of Mongolian tribes. But since the birth of Mongolian characters, she has used soft brush (brush) and hard brush (bamboo pen) to write Mongolian calligraphy. This argument can be confirmed in the cultural heritage and historical relics such as copies (written on sheepskin or silk), woodblock prints, inscriptions, seals, plaques, etc. handed down from the Genghis Khan era.

The artistic connotation of calligraphy is extensive and profound. Besides the skills of calligraphy, there are also psychological consciousness, noble ethics and morality, the order of mathematical limits, the rhythm of music, logical speculation of philosophy and the spirit of literature.

Feelings of mood, emotions of joy, anger, sorrow and joy are organically integrated into the hazy color of aesthetic consciousness, forming a vast artistic connotation of calligraphy. It produces a strong artistic effect. Calligraphy is a polygonal art crystallization which expresses rich connotations through external plastic arts.

Characteristic

However, Mongolian calligraphy has its inherent advantages and possibilities in terms of specific aesthetic conditions and requirements. First of all, just like the Mongolian people riding on horseback, Mongolian characters are also letters riding on letters to form the vertical structure of words. Not only does each word have a head, a stem (waist) and a tail, but each letter has a structure similar to that of some part of a human or animal.

For example, the alphabetic structure part of the figurative names such as corners, dialectics and prefixes is behind the stem (Mongolian name waist); the alphabetic structure part of the figurative names such as teeth, hooks, belly and claws is in front of the stem; the left-handed (Mongolian name is front-tail), right-handed (Mongolian name is tail) and other figurative names are under the words; and the single-point, right-handed (Mongolian name is tail) and so on. Two-point isomorphism, such as dripping sweat, can be found on the left or right of the word.

Because Mongolian characters have this unique hieroglyphic structure, such as the use of artistic skills of calligraphy, through artistic conception, ingenious layout and proper writing, will produce endless artistic appeal. Careful observation and taste of those exquisite and vivid writing, those rising horns and swinging tails are like dragons sailing into the sea, swimming in the sky; standing up and braiding like a milkmaid laughing and dancing, Ana graceful; teeth and claws like a tiger rushing to eat, dangerous like a ring; shy belly hook like a wrestling master, jumping into the field, a strong wind; those swinging words are like a horse dragging rod, galloping in. A horseman in the field.

If we appreciate the works with the aesthetic perspective of calligraphy, which cause the formation of vertical lines, horizontal battles, dense, scattered, virtual and real shapes to achieve perfect unity, it will make people enter a kind of aesthetic mood which is both obscure and vivid; some like grass, birds and flowers, give people fresh, natural, simple and vigorous impulse; some like dense forests, pine. The roar of the waves gives people a deep, steady, serious and solemn atmosphere; some like ten thousand horses galloping, smoke rolling, people are overwhelmed by the vigorous, unrestrained, strong and solemn momentum; some like mountains and waterfalls, breathing through the rainbow, making people feel vigorous, tense and magnificent. The profound artistic conception of Mongolian calligraphy is silent music and dynamic picture. It gives people the enjoyment of beauty and the Enlightenment of wisdom. Therefore, Mongolian calligraphy, with its unique writing structure and characteristics, can produce different artistic effects from other ethnic calligraphy.

Although Mongolian calligraphy has its own independent system in its artistic expression means, it naturally affects or absorbs nutrients in the long-term interaction with Chinese culture and art, especially Chinese calligraphy and painting art (ink painting), thus making Mongolian calligraphy have common aesthetic categories in reproduction techniques and forms of expression.

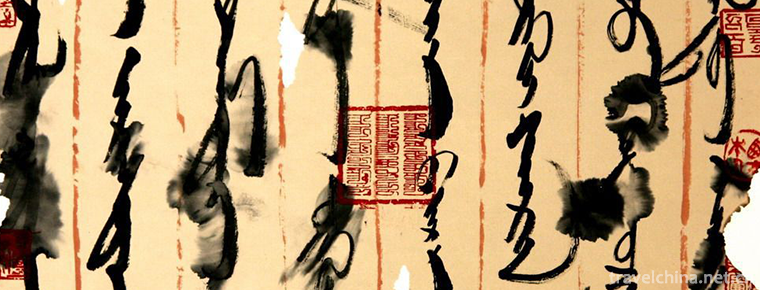

Brushwork

Mongolian traditional calligraphy also pays attention to the skills of moving pens, such as astringent two-way pen, backhand pen, towing pen, effect pen, horizontal pen, etc. In ink, there are full pen, thirsty pen and astringent pen. However, in the past, no matter what brushwork, only the ink is different, but the tradition of no distinction between shade and shade has been broken, and a new way of expressing the same brushwork of shade and shade has emerged. Some are dipped in thick ink before light ink, others are dipped in light ink after full brush, which is not only a change in ink law, but also a product of Mongolian calligraphy which is not confined to the traditional fetters and strives to achieve free will. This method of writing with thick and light ink in the same pen apparently produces artistic style, color, artistic conception and charm that can not be produced by thick ink calligraphy.

For example, works written in different proportions of thick and light ink with full brushes naturally decrease the contrast between black and white, giving people a wonderful feeling of sky and water, clouds and mists; works written in light ink with full brushes, such as flying fairies dancing in crystal and transparent trimmed skirts, make people feel soft, relaxed, harmonious and beautiful, and make calligraphy lines richer. Spirituality and artistic interest. Of course, this artistic effect will also vary according to the different associations of the audience.

The works that unite the above-mentioned techniques of expression with aesthetic ideal and artistic style undoubtedly come from solid skill and knowledge.

The hand of the profound. Lack of down-to-earth and hard-working brushwork skills and brushwork will not only hide the artificial appearance, but also produce a profound artistic conception and rich intrinsic charm of calligraphy. If we neglect the training and sublimation of knowledge and moral sentiment in many aspects, even if the cold window lasts for several years and wears through the inkstone, it will be difficult to break away from the ranks of calligraphers in the end. Therefore, the organic unity of skill and knowledge cultivation is the basis of the vitality of multi-prism art-Mongolian calligraphy art.

Chen Yi of the Yuan Dynasty once said in his book The Change of Hanlin's Key Points: "Happiness, anger and joy have their own scores. Happiness, anger and ease of character, anger and danger, sadness, depression and convergence of character, joy, calm and elegant character, light and heavy feeling, the convergence and ease of word also have shallow depth and infinite change." This is the close relationship between the art of calligraphy and the author's emotional color, and puts forward penetrating views. That is to say, through the shape, style and connotation of calligraphy works, it not only reflects the author's brushwork skill and cultural and moral accomplishment level, but also can perceive the author's exuded emotional color, giving people an aesthetic pleasure.

True calligraphy works of art are the author's mental habits, which are also in line with the scientific conclusions of psychological principles. The change of human emotional color directly or indirectly regulates and controls the whole nervous system. Therefore, the desire for calligraphy creation and the process of calligraphy creation will be affected by the author's emotional impulse. When creating a work, first of all, we must cultivate the emotional color which is compatible with the content of writing words, so as to enter the artistic conception of people's creation, and then generate creative passion, and achieve it at one go.

If we write the words of excitement and pleasure with anger and boredom, there will inevitably be contradictions in the works produced. Wang Xizhi, a great calligrapher in Jin Dynasty (preface to Lanting), and Yan Zhenqing, a great calligrapher in Tang Dynasty (manuscript for offering sacrifices to his nephew), wrote immortal works representing the style of an era driven by strong emotions. However, Wang Xi, a master of calligraphy, failed to write such a well-known masterpiece as the Preface of Lanting. The reason is that the author's emotions are no longer highly unified with the content of his creation as they were when he wrote the Preface of Lanting. Obviously, the author's emotional color is closely related to the success or failure of the art of calligraphy.

In the history of Mongolian calligraphy, there are many excellent works of Lyric calligraphy. The lines in these works can implicitly express the author's joys, sorrows and sorrows, impact the heartstrings of the viewers, infect the viewers and arouse resonance. Even those who do not know Mongolian characters may as well understand the author's aesthetic taste. Mongolian calligraphy is an expressive art that expresses dynamic emotional mood by moulding static literary forms. Like living animals, Mongolian calligraphy is also a life art with flesh and blood and soul.

Inheritance significance

Mongolian calligraphy, with its various forms and far-reaching meanings, has its own unique beauty of form and implication, which most vividly embodies the natural and smart cultural Sui God of Mongolian nationality. Every successful calligraphy work is not a gift from God, nor a money ransom, but a knot that has been comprehended and improved through long and arduous practice.

Mongolian Grammar

-

Tiantai Mountain Scenic Area

Tiantai Mountain Scenic Spot, National AAAAA Class Tourist Spot, National Key Scenic Spot, One of China's Top Ten Famous Mountains, National Eco-tourism Demonstration Zone, Zhejiang Top Ten Tourist Sp

Views: 287 Time 2018-12-07 -

Lang Mountain Scenic Area

Langshan is located in the northwest side of the hinterland of the Yuechengling Mountains, which is the longest in Wuling Mountains. It spans Xinning County and Resource County

Views: 234 Time 2018-12-12 -

Bihai Jinsha Water Paradise

Bihai Jinsha Water Paradise (i.e. Coastal Recreation Park, abbreviated as "Water Paradise") is built outside the flood control wall, along the flood control wall 1313 meters

Views: 470 Time 2019-01-03 -

suyukou national forest park

Suyukou National Forest Park is located in Helan Mountain National Nature Reserve, 50 kilometers northwest of Yinchuan City, capital of Ningxia. It is a national 4A-level tourist attraction.

Views: 182 Time 2019-02-13 -

Flower Drum Opera

Huagu opera, a kind of local opera in China, has the most identical names in the national local opera, usually referring to Hunan Huagu opera. Hubei, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Shaanxi and other

Views: 176 Time 2019-05-04 -

Mulian Opera

Mulian Opera is an ancient opera with religious story "Mulian Save Mother" as its theme, which is preserved in folk activities. It is the first opera that can be tested at present. It is kno

Views: 138 Time 2019-06-06 -

Manufacturing Skills of Inside Lined 1000 Layer Cloth Shoes

Inline Shoe Shoe Shoe Shoe Shoe Shoe Shop was founded in 1853 in Xianfeng, Qing Dynasty. At first, it was specially designed for the royal family and officials at all levels t

Views: 316 Time 2019-06-07 -

Legend of the Three Kingdoms

The legend of the Three Kingdoms is a kind of folk literature which was approved by the State Council and listed in the fourth batch of national intangible cultural heritage list in 2014.

Views: 226 Time 2019-06-12 -

Sayerhao of Tujia Nationality

"Sayeer Hao" of Tujia nationality in Changyang, Hubei Province is a kind of sacrificial song and dance of Tujia nationality in the middle reaches of Qingjiang River valley. "Sayer Haw&q

Views: 388 Time 2019-06-23 -

Long Drum Dance of Yao Nationality

Chinese Yao folk dance. Popular in Guangdong, Guangxi, Hunan and other provinces where Yao people live together, most of them perform on traditional Yao festivals, harvest celebrations, relocation or

Views: 262 Time 2019-07-11 -

Capital University of Economics and Business

Capital University of Economics and Trade was founded in 1956. It was a key university under the municipal authority of Beijing, which was merged and established by the former Beijing School of Econom

Views: 153 Time 2019-09-22 -

Plant resources in Neijiang

Neijiang City is a subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forest belt with mild climate and abundant rainfall, which is suitable for the growth of a variety of trees. There are more than 60 subjects, 110 genera and 190 species. Neijiang is mainly composed of timber forest

Views: 317 Time 2020-12-16